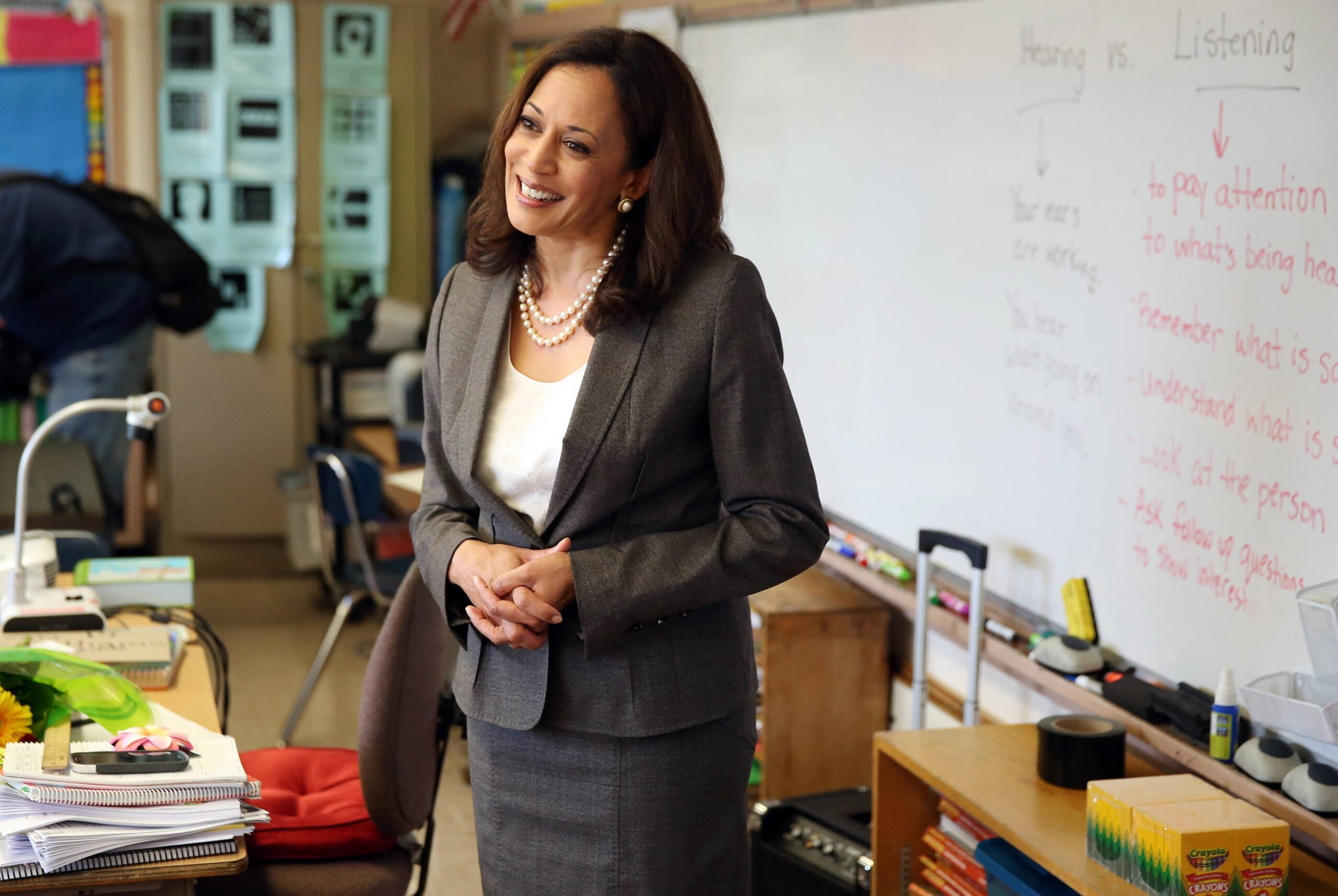

America’s teachers deserve a pay raise and Kamala Harris wants to give it to them.

BY PHIL BERKAW

Outing yourself as a teacher to new acquaintances is often met with responses typically reserved for those in the military: “Thank you for your service.” Or: “Your work makes a difference.” We are not war heroes, but teachers do provide an essential public service for which we are substantially underpaid. In America, the average public school teacher can start anywhere from $31,000 in Montana to $55,000 in New Jersey. In Louisiana, where I taught high school physics for four years, my starting salary was $43,000. Given the 80-hour work weeks I averaged my first year, that’s $13 per hour.

America’s teachers deserve a pay raise and Kamala Harris wants to give it to them. The 2020 presidential candidate has proposed a salary increase that will net the average teacher an additional $13,500 per year. Educators should be thrilled, but U.S. taxpayers should recognize that teachers are not the primary beneficiaries of a potential salary increase. It is our nation’s children. The proposal is likely to increase the diversity of the teacher workforce in addition to improving teacher quality overall.

In a 2015 study, researchers at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education noted that “despite their importance, individuals entering the teaching profession in the United States tend to come from the lower part of the cognitive ability distribution of college graduates.” They found convincing evidence that relatively higher salaries could compel higher-quality candidates to take jobs in education rather than, say, the private sector. In their study, students in these higher-quality candidates’ classrooms also performed better on standardized tests.

While higher pay stands to benefit all public school students, it is especially likely to benefit students of color. At current levels of pay, many individuals who can afford to accept such low salaries are White and have other sources of income. I was one of them. If my car broke down or I couldn’t afford to make rent, I knew I could rely on the financial support of my family. Similar to how wealthier college students can afford to take unpaid internships in New York City while their less wealthy counterparts can’t, I was comfortable taking a lower-paid teaching position after college because I knew I was insulated from financial catastrophe.

Would-be teachers from lower-income backgrounds may not have the luxury to make that choice—and given the legacy of racial inequality in the US, they are statistically more likely to be people of color. I don’t mean to suggest that all teachers of color are economically disadvantaged. This is obviously not true. Still, increasing salaries is likely to broaden the spectrum of potential teacher applicants. In her article in the Atlantic, Amanda Machado notes that teachers from low-income backgrounds are sometimes “the ones responsible for supporting [their] families, not the other way around…I knew several teachers of color who had the responsibility of sending money home or otherwise contributing to family expenses.” She also describes a desire among minority graduates to select a career that indicates you have truly “made it.” An average starting salary of $39,000 fails to satisfy that desire.

It’s not surprising, then, that 62 percent of Boston Public Schools (BPS) teachers identified as White in 2017 while only 13 percent of BPS students identified themselves as such. Despite substantial evidence that Black students are more likely to graduate from high school and attend college if taught by teachers who look like them, the vast majority of Boston’s students of color are taught by White teachers. Only 20 percent of BPS’s teachers are Black, much to the detriment of Black students. A 2005 study by Thomas Dee of Stanford University found that for Black and Hispanic students, having a teacher of a different race increased the likelihood of their being perceived as “disruptive” by 47 percent and as “inattentive” by 71 percent. Racial biases, both conscious and subconscious, raise the likelihood of discrimination against students of color by their White teachers.

Many cities across the country have attempted to increase the diversity of their teachers to little or no avail. To its credit, Boston has launched several initiatives aimed at reducing racial disparities, but with extremely limited success. Smart public policy and innovative programs can make a difference, but sometimes it really is just about money. Kamala Harris may have stumbled into a viable solution for a previously intractable problem: ensuring our students see successful versions of themselves in their teachers.

Phil is a second-year Masters in Public Policy student at the Harvard Kennedy School. He studies innovation in local government and was previously a high school science teacher in New Orleans, Louisiana.