The authors of this article partnered with seven juvenile detention centers across the country to obtain an unprecedented snapshot of youth in custody to determine if lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming and transgender (LGBQ/GNCT) youth are overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. Specifically, the authors were interested in understanding how disparate system practices impacted youth with multiple identities across race, sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression (SOGIE).

Alameda and Santa Clara counties in California; Cook County, Illinois; Jefferson County, Alabama; Jefferson and New Orleans parishes, Louisiana; and Maricopa County, Arizona all participated in the study and provided the authors a total of 1400 completed, one-time surveys to the authors.

This paper presents new data from the surveys and provides recommendations to the field for policy and practice reforms to promote fair and equitable treatment of LGBQ/GNCT youth in the juvenile justice system.

Literature Review

A growing body of literature suggests that lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming and transgender youth—particularly those of color–are exposed to social and systemic experiences that drive their overrepresentation in the juvenile justice system.

One of the first articles on the overrepresentation of LGBQ/GNCT youth found that 15 percent of the justice-involved youth who participated in an anonymous survey indicated they identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming or transgender (Irvine, 2010, 686). Moreover, 92% of the youth in the survey—whether straight or LGBQ/GNCT—were of color (Irvine, 2010, 683). These numbers are likely to be conservative because of the risks of harassment and sbuse youth potentially face with coming out while incarcerated. Many youth may decide not to disclose a non-heterosexual identity or may falsely identify as heterosexual in order to protect themselves (Majd et. al., 2009, 44).

The following literature review provides an overview of research on the forces that drive this overrepresentation.

Highlighting race & birth sex

Despite the national success of juvenile decarceration across all youth, the proportion of youth of color in the juvenile justice system continues to grow at a disproportionately alarming rate. Youth of color represented 43 percent of detained youth in 1985. That number rose to 56 percent in 1995 and to 80 percent in 2012 (Davis, Irvine, and Ziedenberg, 2014a). Overall general population data shows that the number of Black youth especially does not justify their incarceration numbers nor does crime data show a spike in violent crime. In 2006, only 31 percent of incarcerated youth, including youth of color, were being punished for violent crimes (Mendel 2009). This means that 69 percent of detained youth were incarcerated for property crimes, drug offenses, probation violations, or status offenses such as curfew violations and truancy (Mendel 2009).

The court system further reinforces disparities. Data reveal White youth are less likely to be detained and formally processed in the juvenile justice system than youth of color who are charged with the same crime (Mariscal and Bell 2011). Once a case makes it to court, Blacks and Latinos receive harsher sentences than White people and are more likely to receive gang enhancements, lengthening their lengths of stay in detention (Johnson and Johnson 2012; Van Hofwegen 2009; Schlesinger, 2005; Demuth 2003; Steffensmeier and Demuth 2000).

Few studies exist showing how race, gender, and sexual orientation combine to drive young people into the juvenile justice system, though there are a few exceptions. Morris (2012, 2013) addresses the intersection of race and birth sex, finding that girls of color are becoming overrepresented in the juvenile justice system and now have some of the highest rates of suspension and incarceration amongst their peers (Morris, 2013, 1). She attributes these patterns to a cycle in which black girls are victimized at home or school, respond to the trauma publicly in ways that are perceived as disruptive, and are then punished through school discipline and the justice system rather than being referred to support services (Education Week, 2016, 1).

How social responses to sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression drive youth’s involvement in the juvenile justice system

LGBQ/GNCT youth are also driven into the justice system along a pathway from trauma to punishment. Research reveals a pathway of trauma, family conflict, social isolation and exposure to multiple punitive systems. LGBQ/GNCT youth experience higher rates of neglect, abuse, and rejection from family members than their straight counterparts (Valentine, 2008; Saewyc et. al., 2006; Witbeck et. al., 2004; Savin-Williams, 2004; Earls, 2002; Cochran et. al., 2002). These youth are also more likely to be removed from their home for abuse or neglect, suspended or expelled from school, and to be homeless. (Irvine and Canfield 2014, 1; Garnette et al. 2011, 158-161; Irvine 2010, 691-695).

Rejection of youths’ SOGIE by parents, guardians, or placements in the foster care system leads to high rates of running from home and homelessness among LGBQ/GNCT youth (Garnette et. al. 2011, 160-161; Irvine, 2010, 692-693). Once youth are on the street, they may engage in sex work or other informal economies for survival (Majd et. al., 2009; Jones et. al., 2014, Dank et. al., 2015; Irvine, 2010, 694). Survival crimes expose LGBQ/GNCT youth to the possibility of juvenile justice involvement (Majd, 2009; Irvine et. al. upcoming). In fact, when it comes to juvenile justice system involvement, Himmelstein and Brückner, 2011 found that youth who experience same-sex attraction and youth who self-identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual are more likely to be stopped by the police, arrested, and convicted of crimes when engaging in the same behaviors as straight youth.

How disparate system responses exacerbate the overincarceration of LGBQ/GNCT youth

For many LGBQ/GNCT youth of color, run-ins with law enforcement are not out of the ordinary (Dank et. al, 2015). Many LGBQ/GNCT youth of color tell traumatic stories of run-ins with law enforcement. Gender nonconforming and transgender youth of color are harassed more often than their white and gender conforming peers (Irvine et. al 2015, 103-106). For example, police are more likely to use homophobic and transphobic slurs when interacting with transgender people of color and more likely to arrest transgender people of color when they are calling for help. (Irvine et. al, 2015, 103-106). Additionally, gender nonconforming Black girls are stopped for assumed gang affiliation or drug possession (Castro, 2016). It is thus submitted that racial and SOGIE stereotypes exacerbate the experiences of system-involvement for LGBQ/GNCT youth of color.

Once LGBQ/GNCT youth are brought into a secure juvenile facility, they may be subject to verbal and physical assaults and discrimination by facility staff and other youth residents (Valentine 2008). Beck (2010) found that 10 percent of LGBT youth were sexually assaulted by other youth in facilities, compared to 1.5 percent of straight youth. Problems often arise because departments do not commit to training staff on how to appropriately protect LGBQ/GNCT youth in confinement (Garnette et. al., 2011). When a youth enters a facility, probation uses actuarial instruments to collect data about romantic relationships, linkages to school, and family conflict (Garnette et. al, 2011). This information is designed to guide placement decisions and the selection of treatment programs that can help address the difficulties youth are facing. Unfortunately, fewer than 25 jurisdictions use instruments that ask questions that allow youth to disclose non-heterosexual identities and same-sex relationships (Bowman, 2017, 1). Probation officers miss a crucial opportunity to learn if a young person’s identity places them are risk for abuse or harassment in the facility and if the behavior that warranted their arrest is rooted in conflict around their SOGIE.

LGBQ/GNCT youth are also susceptible to other harmful practices while in detention. For example, standard practice for facilities is to house all inmates and residents according to their sex assigned at birth (i.e., their genitalia). This forces transgender and gender non-conforming youth to be placed in housing units with the opposite gender, wear clothing that does not reflect their present gender identity, and places them at risk for harassment because their gender expression does not match the other inmates’ or residents’ in the housing unit. Some facilities may not place transgender and gender nonconforming youth with other youth at all and instead will house them alone in isolation where they have limited interaction with other youth and staff to avoid conflict. (Majd, 2009).

Release from secure facilities offers little reprieve from harassment and abuse. As LGBT youth are more likely to have languished in detention for longer than their heterosexual and cisgender peers, they are at increased risk of abuse, injury, and trauma (Garnette, et al. 2011, Majd et al, 2009). LGBT youth may also have difficulty successfully meeting their probation terms, such as obeying their parents/guardians, attending school on time every day, and attending a community-based organization (Garnette et al. 2011). Terms of probation can be challenging for LGBQ/GNCT youth who may not have supportive families or are experiencing SOGIE-related abuse at home, are unsafe at school due to bullying, and cannot find community-based organizations that are affirming of their multiple identities and prepared to address their system experiences (Garnette et. al., 2011). It is suggested that for LGBQ/GNCT youth, meeting their probation terms may require surviving in unsafe spaces.

New National Survey Findings

This article reports on findings from an updated national survey of detention halls around the country. The survey results show that, overall, 20 percent of youth in the detention centers that were surveyed identified as LGBQ/GNCT. The differences across current gender identity, however, are stark: while 13 percent of boys identify as GBQ/GNCT, 40 percent of girls identify as LBQ/GNCT. Additionally, 85% of these LGBQ/GNCT youth are of color.

Methods

Probation departments administered surveys within their own halls, ranches, and camps. Probation chiefs were tasked with identifying staff members to serve as research liaisons for their departments. Each liaison participated in a training facilitated by the authors that provided context for the need to conduct this research and how to administer the research while protecting the participants.

Following the trainings, each site determined an appropriate time to survey each youth in their facilities according to their size, programming and staff availability. Incoming youth were surveyed four to eight hours after entering the facility and the other youth were surveyed on one day either during school or mealtime.

The one-page survey instrument and a one-page consent form sheet were written at a fifth-grade reading level and were offered in both English and Spanish. The consent forms were read aloud by the research liaisons and only required youth to mark an “X” in a box in lieu of their signatures to maintain anonymity and ensure protection. Youth were not required to complete the survey at all or in its entirety, and were not required to disclose their decision to participate to the research liaisons. Once the youth completed the surveys, they folded them up and sealed them in envelopes, which were mailed back to the authors.

Research sites were Alameda and Santa Clara counties, California; Cook County, Illinois; Jefferson County, Alabama; Jefferson and New Orleans parishes, Louisiana; and Maricopa County, Arizona. Each site collected surveys during a period of two to four months or until they collected a minimum of 200 youth surveys.

Respondents varied across gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation:

- The majority of respondents identified as cisgender males. Seventy-seven percent of respondents identify as cisgender males, 22.4 percent of respondents identify as cisgender female identity, and .6 percent of respondents have a different gender identity.

- Youth of color are overrepresented within the incarcerated LGBQ/GNCT population: 85 percent of respondents were youth of color. Broken down, 37.9 percent of respondents are African American or Black, 1.7 percent of respondents are Asian, 32.6 percent of respondents are Latino, 2.3 percent of respondents were Native American, 13.1 percent of respondents are white, 11.8 percent of respondents had a mixed race or ethnic identity, and .6 percent of respondents had another race or ethnic identity.

- Youth of color disclosed being LGBQ/GNCT at the same rate as white youth.

- 20 percent of respondents identified as either lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming or transgender.

- 7.5 percent of respondents are straight and gender nonconforming or transgender;

- 4.8 percent of respondents are lesbian, gay, or bisexual and gender nonconforming or transgender;

- and 7.7 percent of respondents are lesbian, gay, or bisexual and gender conforming.

Gender differences

We explain these differences in disclosure rates across race in more detail below.

Boys

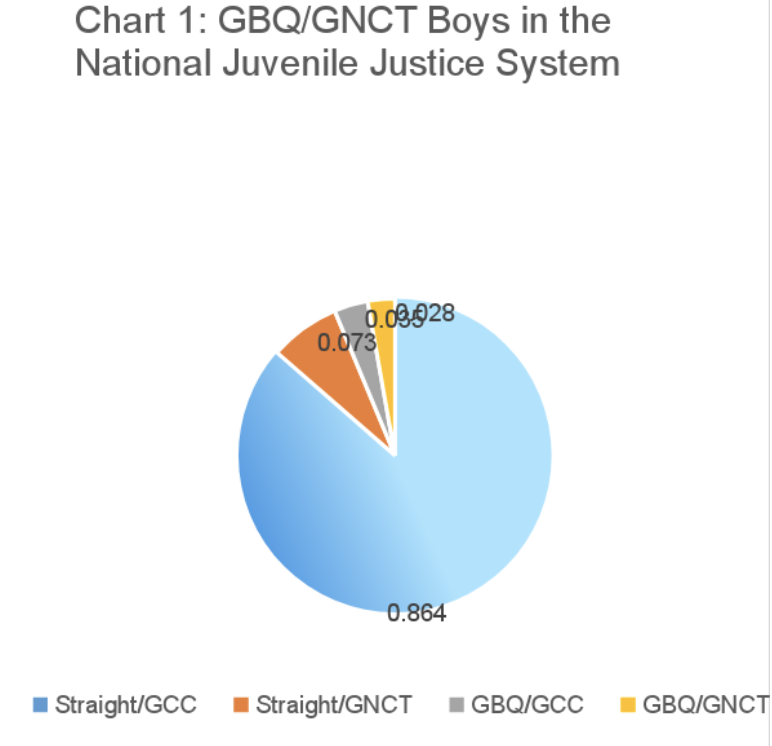

Disaggregating sexual orientation from gender identity provides a more detailed description of incarcerated youth. Chart 1 splits boys into four groups:

- 86.4 percent of boys are straight, gender conforming, and cisgender (these are straight boys who behave and/or dress in the way that society expects them to);

- 7.3 percent of boys are straight and gender nonconforming (these are straight boys who behave and/or dress in a way that is more feminine than society expects them to);

- 3.5 percent of boys are gay, bisexual, and questioning, gender conforming, and cisgender (these are gay boys who behave and/or dress in the way society expects them to); and

- 2.8 percent of boys are gay, bisexual, and questioning and gender nonconforming (these are gay boys who behave and/or dress in a way that is more feminine than society expects them to);

- Added up, this is 13.6 percent of boys that are GBQ/GNCT.

Girls

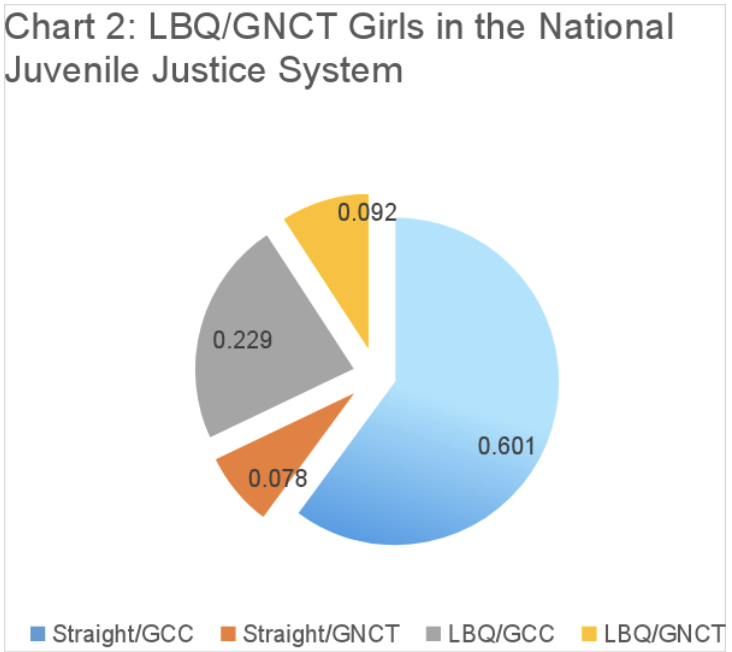

Chart 2 uses the same methodology for girls:

- 60.1 percent of girls are straight, gender conforming, and cisgender;

- 7.8 percent of girls are straight and gender nonconforming or transgender;

- 22.9 percent of girls are lesbian, bisexual, and questioning, gender conforming, and cisgender and;

- 9.2 percent of girls are lesbian, bisexual, questioning, and gender nonconforming or transgender;

- Added together, this is 39.9 percent of girls in California who are LBQ/GNCT.

Additionally, the survey found that LGBQ/GNCT youth are approximately twice as likely to have a history of running away and homelessness–prior to entering the justice system–compared with their straight, gender conforming and cisgender peers.

Recommendations to Policy Researchers and Advocates

LGBQ/GNCT youth of color are resilient. They exude confidence, authenticity, and courage each day they step outside of their doors. However, they also carry the heavy burden that comes along with being LGBQ/GNCT. LGBQ/GNCT youth endure threats to their safety, well-being and healthy development by family rejection, school bullying, and system involvement. It is imperative that juvenile justice stakeholders do no further harm to these youths while they are in custody and that they seek to be affirming of both their racial/ethnic identities and their SOGIE.

There are several measures that juvenile justice stakeholders, practitioners, and community-based organizations can take to successfully respond to the unique needs of system-involved LGBQ/GNCT youth of color. These suggestions are in detail below.

Developing anti-discrimination policies that promote equitable treatment of LGBQ/GNCT youth

Juvenile probation departments should partner with local LGBT centers or advocates to draft and adopt anti-discrimination policies that enforce the safety of LGBQ/GNCT youth in the system and ensure their equitable and respectful treatment. Policies must protect LGBQ/GNCT youth from harassment and abuse by other youth residents, staff, and contracted services providers on the basis of their actual or perceived SOGIE. A comprehensive policy should include:

- Respectful communication with and about LGBQ/GNCT youth.

- Meaningful and accessible grievance procedures for youth to confidentially report abuse, harassment or discrimination without risk of retaliation.

- Use of preferred names and pronouns.

- Housing and placement decisions on a case-by-case basis that consider youths’ current gender identities rather than the sex assigned at birth. This is particularly important for transgender youth who have transitioned to a gender other than their birth sex.

- Pat downs and searches of transgender and gender nonconforming youth by staff members that are of the youths’ same gender identity.

- Accommodations that ensure the privacy and safety of transgender youth in showers, changing clothes, etc.

- Provision of transition-related medical needs of transgender youth.

Policies should be developed in collaboration with advocates/community members, line staff and decision-makers. Advocates have a deep understanding of the experiences of LGBQ/GNCT youth and can provide context and insight into the unique needs of LGBQ/GNCT youth outside of confinement. Buy-in from line- staff is equally important as implementation and adherence to the policy is more likely to be successful if staff have been given meaningful roles in the policy’s development.

Additionally, agencies and organizations should align their policies with state and federal laws and regulations. For example, the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) is a set of federal standards that have identified LGBTI inmates and residents as a priority population for protection from sexual victimization. The standards provide detailed guidance on the appropriate treatment of LGBTI searches, housing, clothing, medical treatment and programming.

Improving intake assessments to include SOGIE questions

Juvenile facilities, probation departments and community-based organizations commonly assume they are not serving LGBQ/GNCT youth (Irvine 2010). It is imperative that these entities know how the youth in their care identify to effectively respond to their needs, understand the complexity of their experiences, and ensure that any referrals are culturally affirming. Additionally, jurisdictions that collect SOGIE data can make better, data-driven decisions to mitigate disparities and ensure reform efforts target populations that are in most need.

Jurisdictions should consider updating their intake and booking processes to include SOGIE data questions which would guarantee that each youth is asked how they identify when they enter a facility. It is important that the youth who cycle in and out of the secure confinement are asked each time they return as answers may change between stays.

Asking questions about SOGIE is particularly important as most LGBQ youth are gender conforming. This means they do not fit the physical stereotypes of someone who identifies as gay or lesbian and may go unnoticed when it comes to appropriate referrals. By universally asking all youth about their sexual orientation and gender identity, a systematic practice with several benefits can be created. Placing the onus of starting the conversation about SOGIE should be placed on the adult professionals rather than burdening youth with the risks of self-disclosing. Finally, as youth begin to disclose more frequently, the visibility of LBGQ/GNCT youth is increased, making justice agencies even safer.

Providing training and technical assistance to all probation personnel

Juvenile justice reform that is affirming of youths’ race/ethnicity and SOGIE cannot happen without education and training and ongoing education for facility staff. Staff often want to “do the right thing” but feel out of touch with the community or believe it is inappropriate to discuss youths’ SOGIE. Juvenile probation departments can support their staff in becoming comfortable and skilled at interacting with LGBQ/GNCT youth in custody by providing training to all department staff by a skilled trainer/facilitator.

Training and coaching should cover a variety of topics that would increase general understanding of LGBQ/GNCT youth including:

- General background on the experiences of LGBQ/GNCT; including risk factors for systems involvement

- Respectful language, engagement and nonverbal communication

- Collecting SOGIE data

- Biases, fears, and misunderstandings

- The intersections of race/ethnicity, SOGIE, class, and system-involvement

- Identifying and vetting services to ensure appropriate placement of LGBQ/GNCT youth

Technical assistance should be offered following the training so that facilities have real-time access to expert advice as challenges arise.

Expanding gender responsive programming to be affirming of various gender expressions

In the mid-2000’s, the field of juvenile justice began to promote “gender- specific” or “gender-responsive” programming with the intention of improving services for girls. Researchers argued that programs were inappropriately geared towards boys and needed to be specifically tailored for girls (Acoca, 1998; Sherman 2005; Irvine, Canfield, and Roa, 2017). One excellent example is Girls Circle. This curriculum was developed to provide support groups for girls in the justice system. Each meeting is structured to have a welcome ritual and to then dive into discussions of relationships, drug use, and trauma (Irvine and Roa, 2010). The same organization has more recently developed a similar curriculum for boys called “One Circle.”

Typically, youth are referred to gender-specific programs based on their birth sex. In contrast, under the Prison Rape Elimination Act Standards, justice professionals make housing decisions for youth based on their current gender identity—which may not match a young person’s birth sex. The field of community supervision has not yet followed the practice of making decisions based on gender identity or expression.

There are unintended consequences to sending a gender nonconforming young person to a gender-specific program based on birth sex. While all youth should have some agency in deciding what programs that are referred to, it is especially important that gender-nonconforming and transgender youth be given the opportunity to participate in activities or programs that align with their current gender identities. For example, a gender non-conforming girl who must take parenting classes may not identify as her child’s “mother” and rather would feel more comfortable and supported in a parenting class designed for fathers. Every effort should be made to enroll her into a class and an environment that speaks to her identity and sets her up for success.

References

Acoca, Leslie. 1998. Outside/inside: The violation of American girls at home, on the streets, and the juvenile justice system. Crime and Delinquency. 44: 561-589.

Beck, Allen J., Paige M. Harrison, and Paul Guerino. 2010. “Sexual Victimization in Juvenile Facilities Reported by Youth 2008–09.” http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov /index.cfm?ty_pbdetail&iid_2113.

Bowman, Michela. 2017. Informal correspondence based on requests for technical assistance from the Prison Rape Elimination Act Resource Center.

Castro, Estavaliz. 2016. Informal correspondence based on 100 interviews with girls of color who are assumed to be linked to gangs.

Cochran, Joshua C., and Daniel P. Mears. 2015. “Race, Ethnic, and Gender Divides in Juvenile Court Sanctioning and Rehabilitative Intervention.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 52(2): 181-212.

Dank, Meredith, Jennifer Yahner, Kuniko Mdden, Isela Bañuelos, Lilly Yu, Andrea Ritchie, Mitchyll Mora, Brendan Conner. 2015. Surviving the Streets of New York: Experiences of LGBTQ Youth, YMSM, and YWSW Engaged in Survival Sex. Research Report, Urban Institute, Washington D.C.

Davis, Antoinette, Angela Irvine, and Jason Ziedenberg. 2014. “Stakeholder Views on the Movement to Reduce Youth Incarceration.”

Demuth, S. “Racial and ethnic differences in pretrial release decisions and outcomes: a comparison of hispanic, black and white felony arrestees.” Criminology 41, (2003): 873–908.

Earls, Meg. 2002. “Stressors in the Lives of GLBTQ Youth.” Transitions 14 (4): 1–3. http://www .advocatesforyouth.org/index.php?option_com_con tent&task_view&id_697&Itemid_336

Education Week. Q&A with Monique Morris: The Plight of Black Girls in K-12 Schools. Retrieved 10 March 2017 from: http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2016/06/01/qa-with-monique-w-morris-how-k-12.html

Fantz, Ashley, Holly Yan and Catherine E. Shoichet. Texas pool party chaos: ‘Out of control’ police officer resigns. 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/06/09/us/mckinney-texas-pool-party-video/.

Garnette, Laura, Angela Irvine, Carolyn Reyes, and Shannan Wilber. 2011. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth.” Juvenile Justice: Advancing Research, Policy, and Practice, edited by Francine Sherman and Francine Jacobs. John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ.

Himmelstein, Kathryn E.W., and Hannah Brückner. 2011. “Criminal Justice and School Sanctions Against Nonheterosexual Youth: A National Longitudinal Study.” Pediatrics 127 (1): 48-56.

Irvine, Angela and Jessica Roa. 2010. “When gender specific programs for girls are not culturally competent enough.” Policy brief published by Ceres Policy Research, Santa Cruz, CA.

Irvine, Angela. 2010. “’We’ve Had Three of Them’: Addressing the Invisibility of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Gender Nonconforming Youth In the Juvenile Justice System.” Columbia Journal of Gender and Law 19 (3): 675-701.

Irvine, Angela and Aisha Canfield. 2014. “Survey of National Juvenile Detention Facilities.” Unpublished raw data.

Irvine, Angela and BreakOUT!. 2015. “You Can’t Run From the Police: Developing a Feminist Criminology that Incorporates Black Transgender Women.” Southwestern Law Review Volume 44, Number 3.

Irvine, Angela, Aisha Canfield, and Francine Sherman. Upcoming. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Questioning, and Gender Nonconforming Girls and Boys Are At Elevated Risk of Being Detained or Incarcerated for Prostitution in the California Juvenile Justice System.” Article submitted to the American Journal of Public Health.

Irvine, Angela, Aisha Canfield, and Jessica Roa. 2017. “Developing Gender-Responsive Mental Health Programming For Lesbian, Bisexual, Questioning, Gender Nonconforming, and Transgender (LBQ/GNCT) Girls in the Juvenile Justice System with an Intersectional Lens.” Upcoming chapter in Datchi, Corinne and Julie Ancis, Gender, Psychology, and Justice: The Mental Health of Women and Girls in the Legal System. New York: New York University Press.

Jarrett, Laura. Video shows police pepper-spraying teen girl. http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/22/politics/maryland-police-pepper-spray-teen-girl/. 2016.

Johnson, M. and Johnson, L.A. “Bail: Reforming Policies to Address Overcrowded Jails, the Impact of Race on Detention, and Community Revival in Harris County, TX.” Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy 42, (2012).

Jones, Nikki, and Joshua Gamson, Brianne Amato, Stephany Cornwell, Stephanie Fisher, Phillip Fucella, Vincent Lee, and Virgie Zolala-Tovar. 2014. CSEC REPORT: SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA. Report submitted to the Center for Court Innovation, New York, NY.

Majd, Katayoon, Jody Marksamer, and Carolyn Reyes. 2009. “Hidden Injustice: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth in Juvenile Courts. The Equity Project.”

Movement Advancement Project, Family Equality Council and Center for American Progress, “All Children Matter: How Legal and Social Inequalities Hurt LGBT Families (FULL REPORT), October 2011.

Mariscal, Raquel, and James Bell. 2011. “Race, Ethnicity and Ancestry in Juvenile Justice.” In Juvenile Justice: Advancing Research, Policy, and Practice, edited by Francine Sherman and Francine Jacobs, 111-130. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Mendel, Richard. 2009. “Two Decades of the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative: From Demonstration Project to National Standard.” Annie E. Casey Foundation, Baltimore, MD.

Morris, Monique. 2012. “Race, Gender, and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Expanding Our Discussion to Include Black Girls.” Report for the African American Policy Forum.

Morris, Monique. 2013. Searching for Black Girls in the School-to-Prison Pipeline (blog). http://www.nccdglobal.org/blog/searching-for-black-girls-in-the-school-to-prison-pipeline

Saewyc, Elizabeth, Sandra Pettingel, and Carol Skay. 2006. “Hazards of Stigma: The Sexual and Physical Abuse of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Adolescents in the United States and Canada.” Journal of Adolescent Health 34 (2): 115-116.

Savin-Williams, Ritch C. 1994. “Verbal and Physical Abuse as Stressors in the Lives of Lesbian, Gay Male and Bisexual Youths: Associations With School Problems, Running Away, Substance Abuse, Prostitution, and Suicide.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62(2): 261–269.

Schlesinger, T. “Racial and ethnic disparity in pretrial criminal processing.” Justice Quarterly 22, (2005): 170–192.

Sherman, Francine. 2005. Pathways to Juvenile Detention Reform—Detention Reform and Girls: Challenges and Solutions. Annie. E. Casey Foundation, Baltimore, MD.

Steffensmeier, D. and Demuth, S. “Ethnicity and sentencing in U.S. Federal courts: who is punished more harshly?” American Sociological Review 65, (2000): 705–729.

Stelloh, Tim and Tracy Connor. Video Shows Cop Body-Slamming High School Girl in S.C. Classroom. 2015. http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/video-appears-show-cop-body-slamming-student-s-c-classroom-n451896

Valentine, Sarah E. 2008. “Traditional Advocacy for Non- Traditional Youth: Rethinking Best Interest for the Queer Child.” Michigan State Law Review 1053 (4): 1054–1113.

Van Hofwegen, S.L. “Unjust and Ineffective: A Critical Look at California’s STEP Act.” Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal 18, (2009): 679-702.

Witbeck, Les, Xiaojin Chen, Dan R. Hoyt, Kimberly A. Tyler, and Kurt D. Johnson. 2004. “Mental Disorder, Subsistence Strategies, and Victimization Among Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Homeless and Runaway Adolescents.” Journal of Sex Research 41: 329-342.